Yantras have become increasingly common in the West among those interested in the occult and religious practices of India and Southeast Asia. Yantra is a Sanskrit (Sk) word meaning, “A tool used to control.” In Southeast Asia Yantras are referred to by their Pali (P) equivalent Yanta or in Thai (Th) as Yan. From the Western perspective, a Yan might be considered a “magic charm.” However, it is far more complex. A Yan incorporates the use of holy words, sacred geometry and the magical use of various mediums to make an object of power. The practice of Yan is mutually dependent upon a working knowledge of Mantra (Sk), Tantra (Sk) and astrology. So much so in fact that Yan are sometimes dubbed the physical manifestation of Mantra.

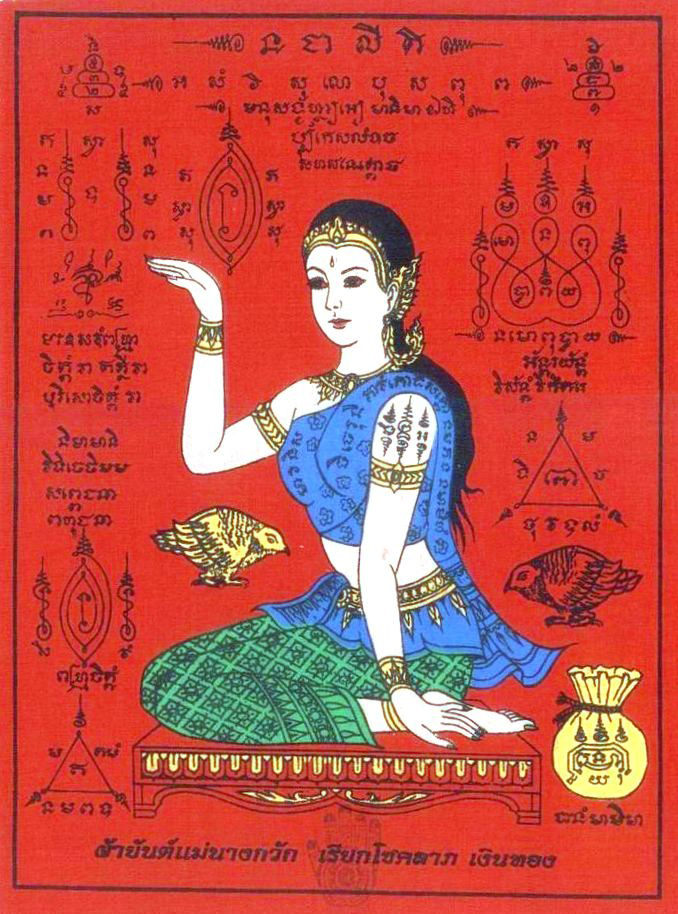

These ancient practices may have been introduced by way of India during the time that Buddhism was brought to Southeast Asia. The Indian methods of Yantra, Mantra, Tantra and astrology combined with the indigenous practices to become the science of Yan found in Thailand today. Although Thailand is a Buddhist country, not all Yan are strictly Buddhist. Elements from Traditional Thai culture, Brahmanism and animism are often incorporated, as the purpose is not always in accord with Buddhist ideals. Yan are employed to achieve a broad spectrum of results. These may range from very mundane and simple needs, such as bringing prosperity to a business, to more spiritual purposes, such as sanctifying a Buddha image for worship. The most common applications in Thailand are for protection, love, wealth and luck.

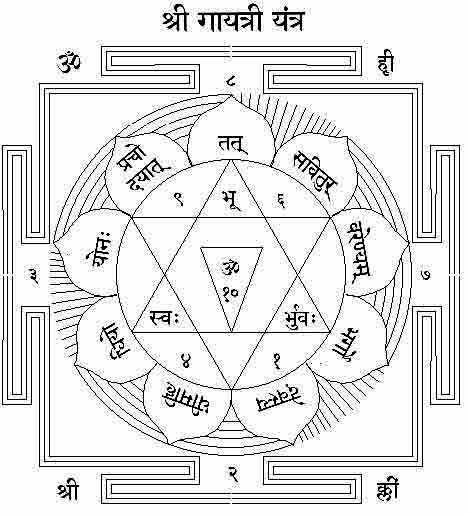

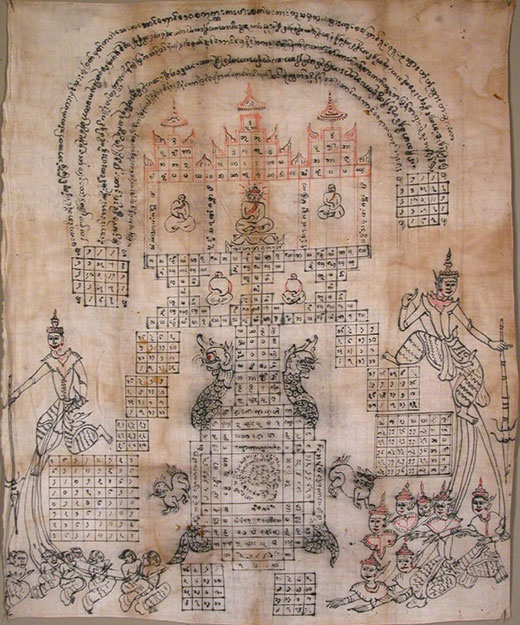

Though generally utilized as preventative or remedial measures, Yan can also be very specific and, in some cases, very dark. For example, there are Yan, which are used to bewitch a member of the opposite sex or to vanquish one’s enemy. While the Buddhist monks who practice these arts frown upon such usage, some lay practitioners will create these Yan despite their karmic consequences. A Yan includes four aspects: geometry, sacred script, holy text and the medium from which it is fashioned. First, I will discuss the geometry of a Yan. Yan are created using various designs, shapes and symbols.

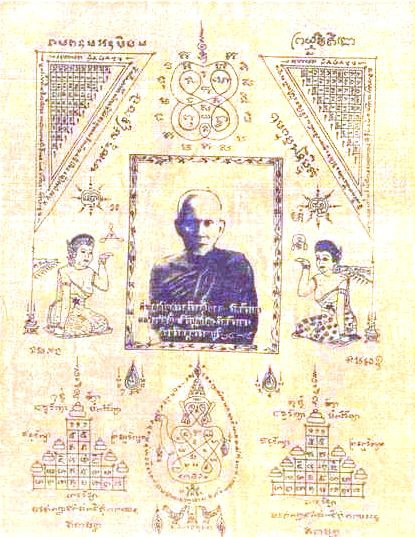

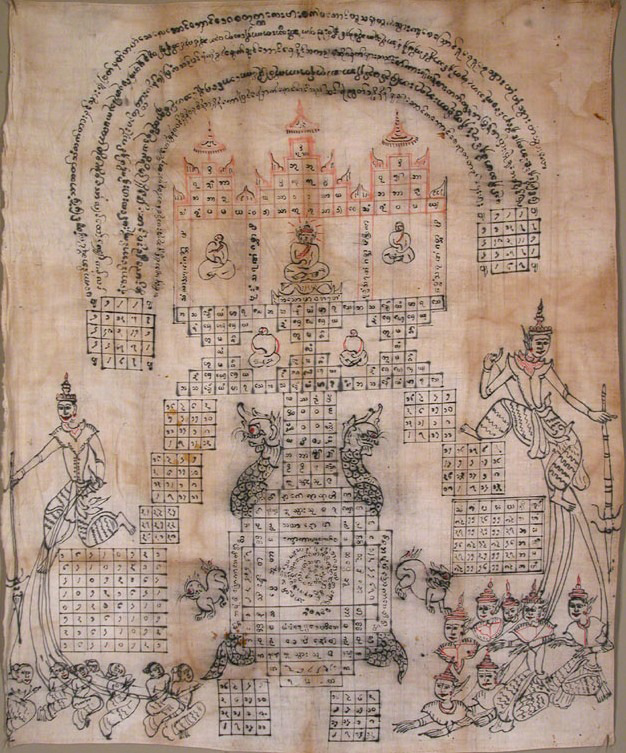

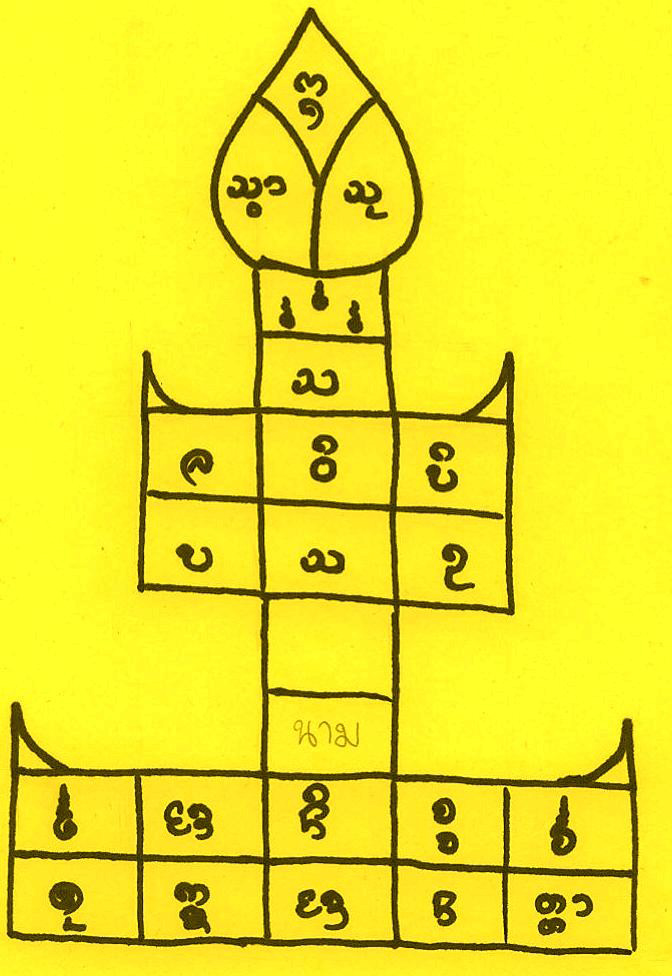

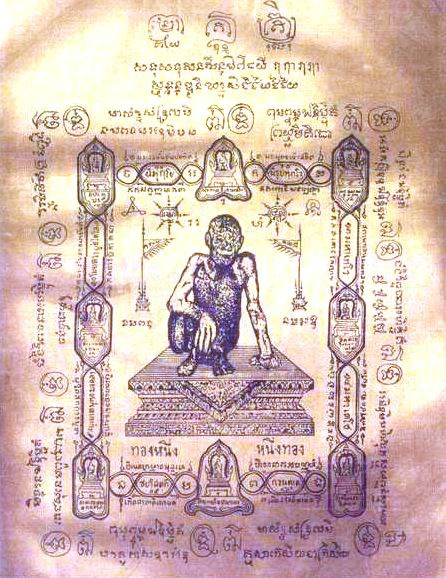

Some utilize squares and triangles, representing the four elements and the Buddhist trinity respectively. Some use circles, which can represent the Sun, Moon or an astrological chart. Other symbols might include Bodhi leaves, wheels or various animals. These images have specific meanings, which are associated with the function of the Yan. Also found in Yan are representations of Buddha images, different gods or prominent Thai figures. These include revered monks and former kings. Magic squares also figure prominently in most Yan. This subject is pertinent to the understanding of Yan but is too complex to further elaborate upon here. I strongly encourage the reader to research this more thoroughly on his/her own. These geometrical patterns lay the groundwork for what the Yan will become.

The sacred script used to compose the Yan is the next aspect we will discuss. Most Yan in Thailand employ a form of Khmer script similar to that used in Cambodia today. Cambodians have a long-standing tradition in Thailand of being a people well versed in the magical arts. This coupled with the fact that Khmer is an ancient language has lent to its status as a highly magical script. Other languages used to create Yan are Lanna, a Northern Thai region, Burmese and, more rarely, Indian scripts. The property most important is the inherent power of the script being used and that it not be a mundane language, which holds less magic. The sacred text employed comprises the third aspect of the Yan. Depending on the purpose and the beliefs of the individual creating the Yan, the words and numbers used may come from different sources. Often a Buddhist Sutta (P) is used in an abbreviated form. In most cases a Gatha (P) or hymn, is taken from the Sutta and is condensed to make a “magic spell.” This method is similar to the creation of a Beeja (Sk) Mantra in the Brahmin tradition. In general, the words used to create a Yan invoke a Buddhist principle, the Triple Gem or something as basic as the four elements. In addition, there are Yan which use spells from the Brahmin tradition to invoke a particular deity. In all circumstances, a greater ideal is being called upon to charge the Yan.

The fourth and final aspect of the Yan is the material used in its creation. This reflects the function of the Yan. The most common medium used is cloth, which may be a variety of colors. Specific colors signify various purposes. For example, a Yan made to increase wealth would be created on a Sunday using red cloth. Other materials include animal skin, paper, money, leaves and bark. Of equal importance, but seldom practiced, is the ink and the instruments used to write the Yan. These utensils can include feathers, tree branches, brushes and pens. The inks are sometimes mixed using ashes, powders or natural dyes. Remaining within these guidelines, the myriad of possibilities is left to the practitioner’s discretion.

At this point I would like to comment on one of the most commonly seen expressions of a Yan that has gained popularity in the West, the traditional Thai tattoos or Sak Yan (Th). These tattoos are hand etched with a “needle.” The practice of tattooing has a long-standing history in Thailand. As Buddhism and the Yan were integrated into ancient Thai culture, a merger with the indigenous methods of tattooing occurred to create the magical tattoos seen today. There is much to say about these tattoos and the benefits and precautions of having one. However, a thorough examination of the subject would require an article of its own. It is enough to mention that these tattoos are one of the most powerful expressions of the Yan seen today.

The method and ritual of making a Yan is very complex and rarely taught to non-initiates. I will give a brief description of the procedure in order to illustrate what it entails. The most important thing, as in any Thai ritual, is to pay respects to ones teacher and those that have come before him/her. The exact objective of the Yan must then be considered. This purpose must be kept at the forefront of the mind throughout the construction of the Yan. Intent is the crucial aspect in determining its ultimate strength and efficacy. Many monks are revered for their powers and ability to make magical items. This is due to their intent, which is steadfast and uninterrupted. The next step is electing the day, time and place of creation. Once again, this is governed by the type of Yan to be produced. Each day of the week has a variety of meanings. For example, Tuesday is optimal for projects related to warfare or protection.

An understanding of astrology is necessary to elect the most auspicious time for such works. Once the practitioner has selected the intention, day, time, materials and utensils, a sanctified area would be chosen to pay respects to the Triple Gem, if Buddhist, and to his/her teacher once more. They would then consecrate the materials and while chanting the specific Mantra, create the Yan. This may also include invoking a spirit or Tevada (Th). The process may have to be repeated several times to fully charge the Yan. Additionally, instructions might be given to the recipient in order to further influence its strength. It should be mentioned, however, that a Yan, no matter how powerful, cannot necessarily overcome one’s Karma. If the Karma of the recipient is too strong in a certain direction, there is nothing that can be done by any outside force to cause a change. However, if ones Karma does lend to the desired results, it is possible for the Yan to have an effect on ones life. This Buddhist perspective represents a fundamental difference from the Brahmin concept of Karma and the power of the Yantra. I thought it would be interesting to include some ways in which Yantra, Mantra and Tantra are used in Thailand for healing. Here is a list of some of the more common practices found today.

- Mantra to remedy burning, redness or irritation in the eyes – the practitioner chants a spell over water and washes their eyes three times.

- Mantra to stop bleeding – uttered 8 times and after each time the practitioner is to blow on the wound.

- Yantra to alleviate sickness, especially of the head and upper body – written on paper, which is burned into ash, mixed with water, and drunk by the patient.

- Yantra written on a leaf of various plants and trees to be taken for appropriate ailments associated with the herb.

I would also like to share a story with you, relayed to me by a monk with whom I study. The monk told me of his home village in Thailand. The village was rather remote and far from any hospitals or doctors. The only healer in the village was a Maw Pao (Th), a “blowing” doctor. One day, a young boy fell from a tree and broke his arm. The Maw Pao took some holy water and some alcohol, mixed it in his mouth and uttered a magic spell. He then sprayed the mixture onto the young boys arm and chanted a few more words. In just one week, the boy was climbing again with no signs of injury. This story illustrates to me both the magic and the faith people have in the power of these methods.

Glossary:

Beeja (Mantra): Beeja, literally seed in Sanskrit. A Beeja Mantra is a Mantra that has been condensed to its root meaning, i.e. the seed from which the larger Mantra grows.

Bodhi Leaf: The leaf from the Bodhi Tree, or Tree of Enlightenment, under which Gotama Siddhattha attained Buddhahood.

Gatha: A poem or hymn often used in chanting.

Mantra: A word or group of words of power, usually invoking a deity.

Sutta: One of the Three Baskets of Buddhist texts; the direct discourses of the Buddha.

Tantra: The ritual use of sacred items in conjunction with Mantra, such as Rudraksha beads.Tevada: Heavenly beings or gods.

I would like to pay my respects and thank my teacher, Phra Ajahn Sukit for sharing his knowledge with me. My thanks also goes out to Ms. Gabrielle Simon for helping with editing.

Written by Yogi Somānanda, translation by Reusi Bhālacandra

No Comments